Covariant formulation of classical electromagnetism

| Articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

The covariant formulation of classical electromagnetism refers to ways of writing the laws of classical electromagnetism (in particular, Maxwell's equations and the Lorentz force) in a form that is manifestly invariant under Lorentz transformations, in the formalism of special relativity using rectilinear inertial coordinate systems. These expressions both make it simple to prove that the laws of classical electromagnetism take the same form in any inertial coordinate system, and also provide a way to translate the fields and forces from one frame to another. However, this is not as general as Maxwell's equations in curved spacetime or non-rectilinear coordinate systems.

This article uses the classical treatment of tensors and Einstein summation convention throughout and the Minkowski metric has the form diag(+1, −1, −1, −1). Where the equations are specified as holding in a vacuum, one could instead regard them as the formulation of Maxwell's equations in terms of total charge and current.

For a more general overview of the relationships between classical electromagnetism and special relativity, including various conceptual implications of this picture, see Classical electromagnetism and special relativity.

Covariant objects

Preliminary four-vectors

Lorentz tensors of the following kinds may be used in this article to describe bodies or particles:

- four-displacement: <math display="block">x^\alpha = (ct, \mathbf{x}) = (ct, x, y, z) \,.</math>

- Four-velocity: <math display="block">u^\alpha = \gamma(c,\mathbf{u}) ,</math> where γ(u) is the Lorentz factor at the 3-velocity u.

- Four-momentum: <math display="block">p^\alpha = ( E/c, \mathbf{p}) = m_0 u^{\alpha} </math> where <math>\mathbf{p}</math> is 3-momentum, <math>E</math> is the total energy, and <math>m_0</math> is rest mass.

- Four-gradient: <math display="block">\partial^{\nu} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{\nu}} = \left( \frac{1}{c} \frac{\partial}{\partial t}, - \mathbf{\nabla} \right) \,,</math>

- The d'Alembertian operator is denoted <math> {\partial}^2 </math>, <math display="block">\partial^2 = \frac{1}{c^2} {\partial \over \partial t}{ \partial \over \partial t} - \nabla^2.</math>

The signs in the following tensor analysis depend on the convention used for the metric tensor. The convention used here is (+ − − −), corresponding to the Minkowski metric tensor: <math display="block">\eta^{\mu \nu}=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix}</math>

Electromagnetic tensor

The electromagnetic tensor is the combination of the electric and magnetic fields into a covariant antisymmetric tensor whose entries are B-field quantities.<ref name=Vanderlinde>Vanderlinde, Jack (2004), classical electromagnetic theory, Springer, pp. 313–328, ISBN 9781402026997</ref> <math display="block">F_{\alpha \beta} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & E_x/c & E_y/c & E_z/c \\ -E_x/c & 0 & -B_z & B_y \\ -E_y/c & B_z & 0 & -B_x \\ -E_z/c & -B_y & B_x & 0 \end{pmatrix}</math> and the result of raising its indices is <math display="block">F^{\mu \nu} \mathrel{\stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}} \eta^{\mu \alpha} \, F_{\alpha \beta} \, \eta^{\beta \nu} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -E_x/c & -E_y/c & -E_z/c \\ E_x/c & 0 & -B_z & B_y \\ E_y/c & B_z & 0 & -B_x \\ E_z/c & -B_y & B_x & 0 \end{pmatrix} \,.</math> where E is the electric field, B the magnetic field, and c the speed of light.

Four-current

The four-current is the contravariant four-vector which combines electric charge density ρ and electric current density j: <math display="block">J^{\alpha} = ( c \rho, \mathbf{j} ) \,.</math>

Four-potential

The electromagnetic four-potential is a covariant four-vector containing the electric potential (also called the scalar potential) ϕ and magnetic vector potential (or vector potential) A, as follows: <math display="block">A^{\alpha} = \left(\phi/c, \mathbf{A} \right)\,.</math>

The differential of the electromagnetic potential is <math display="block">F_{\alpha \beta} = \partial_{\alpha} A_{\beta} - \partial_{\beta} A_{\alpha} \,.</math>

In the language of differential forms, which provides the generalisation to curved spacetimes, these are the components of a 1-form <math>A = A_{\alpha} dx^{\alpha}</math> and a 2-form <math display="inline">F = dA = \frac{1}{2} F_{\alpha \beta} dx^{\alpha} \wedge dx^{\beta}</math> respectively. Here, <math>d</math> is the exterior derivative and <math>\wedge</math> the wedge product.

Electromagnetic stress–energy tensor

The electromagnetic stress–energy tensor can be interpreted as the flux density of the momentum four-vector, and is a contravariant symmetric tensor that is the contribution of the electromagnetic fields to the overall stress–energy tensor: <math display="block">T^{\alpha\beta} = \begin{pmatrix} \varepsilon_{0} E^2/2 + B^2/2\mu_0 & S_x/c & S_y/c & S_z/c \\ S_x/c & -\sigma_{xx} & -\sigma_{xy} & -\sigma_{xz} \\ S_y/c & -\sigma_{yx} & -\sigma_{yy} & -\sigma_{yz} \\ S_z/c & -\sigma_{zx} & -\sigma_{zy} & -\sigma_{zz} \end{pmatrix}\,,</math>

where <math> \varepsilon_0 </math> is the electric permittivity of vacuum, μ0 is the magnetic permeability of vacuum, the Poynting vector is

<math display="block">\mathbf{S} = \frac{1}{\mu_{0}} \mathbf{E} \times \mathbf{B} </math>

and the Maxwell stress tensor is given by <math display="block">\sigma_{ij} = \varepsilon_0 E_i E_j + \frac{1}{\mu_0} B_i B_j - \left(\frac 1 2 \varepsilon_0 E^2 + \frac{1}{2\mu_0} B^2\right) \delta_{ij} \,.</math>

The electromagnetic field tensor F constructs the electromagnetic stress–energy tensor T by the equation:<ref>Classical Electrodynamics, Jackson, 3rd edition, page 609</ref> <math display="block">T^{\alpha\beta} = \frac{1}{\mu_{0}} \left( \eta^{\alpha \nu}F_{\nu \gamma}F^{\gamma \beta} + \frac{1}{4} \eta^{\alpha\beta}F_{\gamma \nu}F^{\gamma \nu}\right)</math> where η is the Minkowski metric tensor (with signature (+ − − −)). Notice that we use the fact that <math display="block">\varepsilon_{0} \mu_{0} c^2 = 1\,,</math> which is predicted by Maxwell's equations.

Maxwell's equations in vacuum

In vacuum (or for the microscopic equations, not including macroscopic material descriptions), Maxwell's equations can be written as two tensor equations.

The two inhomogeneous Maxwell's equations, Gauss's Law and Ampère's law (with Maxwell's correction) combine into (with (+ − − −) metric):<ref>Classical Electrodynamics by Jackson, 3rd Edition, Chapter 11 Special Theory of Relativity</ref>

while the homogeneous equations – Faraday's law of induction and Gauss's law for magnetism combine to form <math>\partial^{\sigma} F^{\mu \nu} + \partial^{\mu} F^{\nu \sigma} + \partial^{\nu} F^{\sigma \mu} = 0</math>, which may be written using Levi-Civita duality as:

<math>\partial_{\alpha}\left(\tfrac{1}{2}\varepsilon^{\alpha\beta\gamma\delta}F_{\gamma\delta}\right) = 0 </math>

where Fαβ is the electromagnetic tensor, Jα is the four-current, εαβγδ is the Levi-Civita symbol, and the indices behave according to the Einstein summation convention.

Each of these tensor equations corresponds to four scalar equations, one for each value of β.

Using the antisymmetric tensor notation and comma notation for the partial derivative (see Ricci calculus), the second equation can also be written more compactly as: <math display="block"> F_{[\alpha \beta, \gamma]} = 0 .</math>

In the absence of sources, Maxwell's equations reduce to: <math display="block">

\partial^{\nu} \partial_\nu F^{\alpha\beta} \mathrel{\stackrel{\text{def}}{=}}

\partial^2 F^{\alpha\beta} \mathrel{\stackrel{\text{def}}{=}}

{1 \over c^2 }{\partial^2 F^{\alpha\beta} \over {\partial t}^2} - \nabla^2 F^{\alpha\beta} =

0 \,,

</math> which is an electromagnetic wave equation in the field strength tensor.

Maxwell's equations in the Lorenz gauge

The Lorenz gauge condition is a Lorentz-invariant gauge condition. (This can be contrasted with other gauge conditions such as the Coulomb gauge, which if it holds in one inertial frame will generally not hold in any other.) It is expressed in terms of the four-potential as follows:

<math display="block">\partial_{\alpha} A^{\alpha} = \partial^{\alpha} A_{\alpha} = 0 \,.</math>

In the Lorenz gauge, the microscopic Maxwell's equations can be written as:

<math display="block">{\partial}^2 A^{\sigma} = \mu_{0} \, J^{\sigma}\,.</math>

Lorentz force

Charged particle

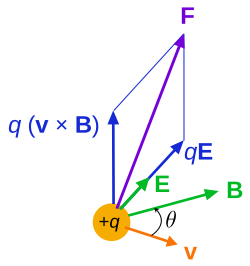

Electromagnetic (EM) fields affect the motion of electrically charged matter: due to the Lorentz force. In this way, EM fields can be detected (with applications in particle physics, and natural occurrences such as in aurorae). In relativistic form, the Lorentz force uses the field strength tensor as follows.<ref>The assumption is made that no forces other than those originating in E and B are present, that is, no gravitational, weak or strong forces.</ref>

Expressed in terms of coordinate time t, it is: <math display="block"> { d p_{\alpha} \over { d t } } = q \, F_{\alpha \beta} \, \frac{d x^\beta}{d t} ,</math>

where pα is the four-momentum, q is the charge, and xβ is the position.

Expressed in frame-independent form, we have the four-force

<math display="block"> \frac{d p_{\alpha}}{d \tau} \, = q \, F_{\alpha \beta} \, u^\beta ,</math>

where uβ is the four-velocity, and τ is the particle's proper time, which is related to coordinate time by dt = γdτ.

Charge continuum

The density of force due to electromagnetism, whose spatial part is the Lorentz force, is given by <math display="block">f_{\alpha} = F_{\alpha\beta}J^{\beta} .</math>

and is related to the electromagnetic stress–energy tensor by <math display="block">f^{\alpha} = - {T^{\alpha\beta}}_{,\beta} \equiv - \frac{\partial T^{\alpha\beta}}{\partial x^\beta}.</math>

Conservation laws

Electric charge

The continuity equation: <math display="block">

{J^\beta}_{,\beta} \mathrel\overset{\text{def}}{\mathop{=}}

\partial_\beta J^\beta =

\partial_\beta \partial_\alpha F^{\alpha \beta}/\mu_0 =

0.

</math> expresses charge conservation.

Electromagnetic energy–momentum

Using the Maxwell equations, one can see that the electromagnetic stress–energy tensor (defined above) satisfies the following differential equation, relating it to the electromagnetic tensor and the current four-vector <math display="block">{T^{\alpha\beta}}_{,\beta} + F^{\alpha\beta} J_\beta = 0</math> or <math display="block">\eta_{\alpha \nu} { T^{\nu \beta } }_{,\beta} + F_{\alpha \beta} J^\beta = 0,</math> which expresses the conservation of linear momentum and energy by electromagnetic interactions.

Covariant objects in matter

Free and bound four-currents

In order to solve the equations of electromagnetism given here, it is necessary to add information about how to calculate the electric current, Jν Frequently, it is convenient to separate the current into two parts, the free current and the bound current, which are modeled by different equations; <math display="block">J^{\nu} = {J^{\nu}}_{\text{free}} + {J^{\nu}}_{\text{bound}} \,,</math> where <math display="block">\begin{align}

{J^{\nu}}_{\text{free}} = \begin{pmatrix} c\rho_{\text{free}}, & \mathbf{J}_{\text{free}} \end{pmatrix} &= \begin{pmatrix} c \nabla \cdot \mathbf{D}, & - \frac{\partial \mathbf{D}}{\partial t} + \nabla\times\mathbf{H}\end{pmatrix} \,, \\

{J^{\nu}}_{\text{bound}} = \begin{pmatrix} c\rho_{\text{bound}}, & \mathbf{J}_{\text{bound}} \end{pmatrix} &= \begin{pmatrix} - c \nabla \cdot \mathbf{P}, & \frac{\partial \mathbf{P}}{\partial t} + \nabla\times\mathbf{M} \end{pmatrix} \,.

\end{align}</math>

Maxwell's macroscopic equations have been used, in addition the definitions of the electric displacement D and the magnetic intensity H: <math display="block">\begin{align}

\mathbf{D} &= \varepsilon_0 \mathbf{E} + \mathbf{P}, \\

\mathbf{H} &= \frac{1}{\mu_0} \mathbf{B} - \mathbf{M} \,.

\end{align}</math> where M is the magnetization and P the electric polarization.

Magnetization–polarization tensor

The bound current is derived from the P and M fields which form an antisymmetric contravariant magnetization-polarization tensor <ref name=Vanderlinde /> <ref>However, the assumption that <math>M^{\mu\nu}</math>, <math>D^{\mu\nu}</math>, and even <math>F^{\mu\nu}</math>, are relativistic tensors in a polarizable medium, is without foundation. The quantity<math display="block">A^{\alpha} = \left(\phi/c, \mathbf{A} \right)\,</math>is not a four vector in a polarizable medium, so <math display="block">F_{\alpha \beta} = \partial_{\alpha} A_{\beta} - \partial_{\beta} A_{\alpha} \,</math> does not produce a tensor.</ref> <ref>Franklin, Jerrold, Can electromagnetic fields form tensors in a polarizable medium?</ref><ref>Gonano, Carlo, Definition for Polarization P and Magnetization M Fully Consistent with Maxwell's Equations</ref> <math display="block">\mathcal{M}^{\mu \nu} = \begin{pmatrix}

0 & P_x c & P_y c & P_z c \\ - P_x c & 0 & -M_z & M_y \\ - P_y c & M_z & 0 & -M_x \\ - P_z c & -M_y & M_x & 0

\end{pmatrix},</math>

which determines the bound current <math display="block">{J^\nu}_\text{bound} = \partial_\mu \mathcal{M}^{\mu \nu} \,.</math>

Electric displacement tensor

If this is combined with Fμν we get the antisymmetric contravariant electromagnetic displacement tensor which combines the D and H fields as follows: <math display="block">

\mathcal{D}^{\mu \nu} =

\begin{pmatrix}

0 & -D_xc & -D_yc & -D_zc \\

D_xc & 0 & - H_z & H_y \\

D_yc & H_z & 0 & -H_x \\

D_zc & -H_y & H_x & 0

\end{pmatrix}.

</math>

The three field tensors are related by:

<math display="block">\mathcal{D}^{\mu \nu} = \frac{1}{\mu_{0}} F^{\mu \nu} - \mathcal{M}^{\mu \nu} </math>

which is equivalent to the definitions of the D and H fields given above.

Maxwell's equations in matter

The result is that Ampère's law, <math display="block">\mathbf{\nabla} \times \mathbf{H} = \mathbf{J}_{\text{free}} + \frac{\partial \mathbf{D}} {\partial t},</math> and Gauss's law, <math display="block">\mathbf{\nabla} \cdot \mathbf{D} = \rho_{\text{free}},</math>

combine into one equation:

_{\text{free}} = \partial_{\mu} \mathcal{D}^{\mu \nu} </math>

|cellpadding |border |border colour = #0073CF }}

The bound current and free current as defined above are automatically and separately conserved <math display="block">\begin{align}

\partial_\nu {J^\nu}_\text{bound} &= 0 \, \\

\partial_\nu {J^\nu}_\text{free} &= 0 \,.

\end{align}</math>

Constitutive equations

Vacuum

In vacuum, the constitutive relations between the field tensor and displacement tensor are: <math display="block">\mu_0 \mathcal{D}^{\mu \nu} = \eta^{\mu \alpha} F_{\alpha \beta} \eta^{\beta \nu} \,.</math>

Antisymmetry reduces these 16 equations to just six independent equations. Because it is usual to define Fμν by <math display="block">F^{\mu \nu} = \eta^{\mu \alpha} F_{\alpha \beta} \eta^{\beta \nu} ,</math> the constitutive equations may, in vacuum, be combined with the Gauss–Ampère law to get: <math display="block">\partial_\beta F^{\alpha \beta} = \mu_0 J^{\alpha}. </math>

The electromagnetic stress–energy tensor in terms of the displacement is: <math display="block">T_\alpha{}^\pi = F_{\alpha\beta} \mathcal{D}^{\pi\beta} - \frac{1}{4} \delta_\alpha^\pi F_{\mu\nu} \mathcal{D}^{\mu\nu} ,</math> where δαπ is the Kronecker delta. When the upper index is lowered with η, it becomes symmetric and is part of the source of the gravitational field.

Linear, nondispersive matter

Thus we have reduced the problem of modeling the current, Jν to two (hopefully) easier problems — modeling the free current, Jνfree and modeling the magnetization and polarization, <math> \mathcal{M}^{\mu\nu}</math>. For example, in the simplest materials at low frequencies, one has <math display="block">\begin{align}

\mathbf{J}_\text{free} &= \sigma \mathbf{E} \, \\

\mathbf{P} &= \varepsilon_0 \chi_e \mathbf{E} \, \\

\mathbf{M} &= \chi_m \mathbf{H} \,

\end{align}</math> where one is in the instantaneously comoving inertial frame of the material, σ is its electrical conductivity, χe is its electric susceptibility, and χm is its magnetic susceptibility.

The constitutive relations between the <math>\mathcal{D}</math> and F tensors, proposed by Minkowski for a linear materials (that is, E is proportional to D and B proportional to H), are: <math display="block">\begin{align}

\mathcal{D}^{\mu\nu}u_\nu &= c^2\varepsilon F^{\mu\nu} u_\nu \\

{\star\mathcal{D}^{\mu\nu}}u_\nu &= \frac{1}{\mu}{\star F^{\mu\nu}} u_\nu

\end{align}</math>

where u is the four-velocity of material, ε and μ are respectively the proper permittivity and permeability of the material (i.e. in rest frame of material), <math>\star</math> and denotes the Hodge star operator.

Lagrangian for classical electrodynamics

Vacuum

The Lagrangian density for classical electrodynamics is composed by two components: a field component and a source component: <math display="block"> \mathcal{L} \, = \, \mathcal{L}_\text{field} + \mathcal{L}_\text{int} = - \frac{1}{4 \mu_0} F^{\alpha \beta} F_{\alpha \beta} - A_{\alpha} J^{\alpha} \,.</math>

In the interaction term, the four-current should be understood as an abbreviation of many terms expressing the electric currents of other charged fields in terms of their variables; the four-current is not itself a fundamental field.

The Lagrange equations for the electromagnetic lagrangian density <math> \mathcal{L}\mathord\left(A_{\alpha}, \partial_{\beta} A_{\alpha}\right)</math> can be stated as follows: <math display="block"> \partial_{\beta}\left[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial (\partial_{\beta}A_{\alpha})}\right] - \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial A_{\alpha}}=0 \,.</math>

Noting <math display="block">\begin{align}

F^{\lambda \sigma} &= F_{\mu \nu}\eta^{\mu\lambda}\eta^{\nu\sigma}, \\

F_{\mu \nu} &= \partial_{\mu} A_{\nu} - \partial_{\nu} A_{\mu}\, \\

{\partial \left(\partial_{\mu} A_{\nu}\right) \over \partial\left(\partial_{\rho} A_{\sigma}\right)}

&= \delta_{\mu}^{\rho} \delta_{\nu}^{\sigma}

\end{align}</math>

the expression inside the square bracket is <math display="block">\begin{align}

\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial (\partial_\beta A_\alpha)}

& = - \ \frac{1}{4 \mu_0}\ \frac{\partial \left(F_{\mu \nu}\eta^{\mu\lambda}\eta^{\nu\sigma}F_{\lambda \sigma}\right)}{\partial \left(\partial_\beta A_\alpha\right)} \\

& = - \ \frac{1}{4 \mu_0}\ \eta^{\mu\lambda}\eta^{\nu\sigma}

\left(F_{\lambda\sigma}\left(\delta^\beta_\mu \delta^\alpha_\nu - \delta^\beta_\nu \delta^\alpha_\mu\right) + F_{\mu\nu}\left(\delta^\beta_\lambda \delta^\alpha_\sigma - \delta^\beta_\sigma \delta^\alpha_\lambda\right) \right) \\

& = - \ \frac{F^{\beta\alpha}}{\mu_0}\,.

\end{align}</math>

The second term is <math display="block">\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial A_{\alpha}} = - J^{\alpha} \,.</math>

Therefore, the electromagnetic field's equations of motion are <math display="block">\frac{\partial F^{\beta\alpha}}{\partial x^{\beta}} = \mu_0 J^{\alpha} \,.</math> which is the Gauss–Ampère equation above.

Matter

Separating the free currents from the bound currents, another way to write the Lagrangian density is as follows: <math display="block"> \mathcal{L} \, = \, - \frac{1}{4 \mu_0} F^{\alpha \beta} F_{\alpha \beta} - A_{\alpha} J^{\alpha}_{\text{free}} + \frac 1 2 F_{\alpha \beta} \mathcal{M}^{\alpha \beta} \,.</math>

Using Lagrange equation, the equations of motion for <math> \mathcal{D}^{\mu\nu}</math> can be derived.

The equivalent expression in vector notation is:

<math display="block"> \mathcal{L} \, = \, \frac 1 2 \left(\varepsilon_{0} E^2 - \frac{1}{\mu_{0}} B^2\right) - \phi \, \rho_{\text{free}} + \mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{J}_{\text{free}} + \mathbf{E} \cdot \mathbf{P} + \mathbf{B} \cdot \mathbf{M} \,.</math>

See also

- Covariant classical field theory

- Electromagnetic tensor

- Electromagnetic wave equation

- Liénard–Wiechert potential for a charge in arbitrary motion

- Moving magnet and conductor problem

- Inhomogeneous electromagnetic wave equation

- Proca action

- Quantum electrodynamics

- Relativistic electromagnetism

- Stueckelberg action

- Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory

Notes and references

Further reading

- The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. II Ch. 25: Electrodynamics in Relativistic Notation

- Einstein, A. (1961). Relativity: The Special and General Theory. New York: Crown. ISBN 0-517-02961-8.

- Misner, Charles; Thorne, Kip S.; Wheeler, John Archibald (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1975). Classical Theory of Fields (Fourth Revised English ed.). Oxford: Pergamon. ISBN 0-08-018176-7.

- R. P. Feynman; F. B. Moringo; W. G. Wagner (1995). Feynman Lectures on Gravitation. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-62734-5.