Electric field

| Electric field | |

|---|---|

Effects of an electric field. The girl is touching an electrostatic generator, which charges her body with a high voltage. Her hair, which is charged with the same polarity, is repelled by the electric field of her head and stands out from her head. | |

Common symbols | E |

| SI unit | volt per meter (V/m) |

| In SI base units | m⋅kg⋅s−3⋅A−1 |

| Articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

An electric field (sometimes called E-field<ref>Roche, John (2016). "Introducing electric fields". Physics Education. 51 (5): 055005. Bibcode:2016PhyEd..51e5005R. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/51/5/055005. S2CID 125014664.</ref>) is the physical field that surrounds electrically charged particles. Charged particles exert attractive forces on each other when their charges are opposite, and repulsion forces on each other when their charges are the same. Because these forces are exerted mutually, two charges must be present for the forces to take place. The electric field of a single charge (or group of charges) describes their capacity to exert such forces on another charged object. These forces are described by Coulomb's law, which says that the greater the magnitude of the charges, the greater the force, and the greater the distance between them, the weaker the force. Thus, we may informally say that the greater the charge of an object, the stronger its electric field. Similarly, an electric field is stronger nearer charged objects and weaker further away. Electric fields originate from electric charges and time-varying electric currents. Electric fields and magnetic fields are both manifestations of the electromagnetic field, Electromagnetism is one of the four fundamental interactions of nature.

Electric fields are important in many areas of physics, and are exploited in electrical technology. For example, in atomic physics and chemistry, the interaction in the electric field between the atomic nucleus and electrons is the force that holds these particles together in atoms. Similarly, the interaction in the electric field between atoms is the force responsible for chemical bonding that result in molecules.

The electric field is defined as a vector field that associates to each point in space the force per unit of charge exerted on an infinitesimal test charge at rest at that point.<ref>Feynman, Richard (1970). The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol II. Addison Wesley Longman. pp. 1–3, 1–4. ISBN 978-0-201-02115-8.</ref><ref>Purcell, Edward M.; Morin, David J. (2013). Electricity and Magnetism (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-107-01402-2.</ref><ref name="Serway" /> The SI unit for the electric field is the volt per meter (V/m), which is equal to the newton per coulomb (N/C).<ref>Le Système international d’unités [The International System of Units] (PDF) (in français and English) (9th ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures, 2019, ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0, p. 23</ref>

Description

The electric field is defined at each point in space as the force that would be experienced by a vanishingly small stationary test charge at that point divided by the charge.<ref name=uniphysics>Sears, Francis; et al. (1982), University Physics (6th ed.), Addison Wesley, ISBN 0-201-07199-1</ref>: 469–70 The electric field is defined in terms of force, and force is a vector (i.e. having both magnitude and direction), so it follows that an electric field may be described by a vector field.<ref name=uniphysics/>: 469–70 The electric field acts between two charges similarly to the way that the gravitational field acts between two masses, as they both obey an inverse-square law with distance.<ref name=Umashankar>Umashankar, Korada (1989), Introduction to Engineering Electromagnetic Fields, World Scientific, pp. 77–79, ISBN 9971-5-0921-0</ref> This is the basis for Coulomb's law, which states that, for stationary charges, the electric field varies with the source charge and varies inversely with the square of the distance from the source. This means that if the source charge were doubled, the electric field would double, and if you move twice as far away from the source, the field at that point would be only one-quarter its original strength.

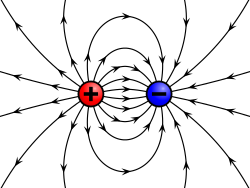

The electric field can be visualized with a set of lines whose direction at each point is the same as those of the field, a concept introduced by Michael Faraday,<ref name="elec_princ_p73">Morely & Hughes (1970), Principles of Electricity (5th ed.), Longman, p. 73, ISBN 0-582-42629-4</ref> whose term 'lines of force' is still sometimes used. This illustration has the useful property that the strength of the field is proportional to the density of the lines.<ref name="Tou">Tou, Stephen (2011). Visualization of Fields and Applications in Engineering. John Wiley and Sons. p. 64. ISBN 9780470978467.</ref> Field lines due to stationary charges have several important properties, including always originating from positive charges and terminating at negative charges, they enter all good conductors at right angles, and they never cross or close in on themselves.<ref name=uniphysics/>: 479 The field lines are a representative concept; the field actually permeates all the intervening space between the lines. More or fewer lines may be drawn depending on the precision to which it is desired to represent the field.<ref name="elec_princ_p73"/> The study of electric fields created by stationary charges is called electrostatics.

Faraday's law describes the relationship between a time-varying magnetic field and the electric field. One way of stating Faraday's law is that the curl of the electric field is equal to the negative time derivative of the magnetic field.<ref name=griffiths>Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-805326-X. OCLC 40251748.</ref>: 327 In the absence of time-varying magnetic field, the electric field is therefore called conservative (i.e. curl-free).<ref name=griffiths />: 24, 90–91 This implies there are two kinds of electric fields: electrostatic fields and fields arising from time-varying magnetic fields.<ref name=griffiths/>: 305–307 While the curl-free nature of the static electric field allows for a simpler treatment using electrostatics, time-varying magnetic fields are generally treated as a component of a unified electromagnetic field. The study of magnetic and electric fields that change over time is called electrodynamics.

Mathematical formulation

Electric fields are caused by electric charges, described by Gauss's law,<ref>Purcell, p. 25: "Gauss's Law: the flux of the electric field E through any closed surface ... equals 1/e times the total charge enclosed by the surface."</ref> and time varying magnetic fields, described by Faraday's law of induction.<ref>Purcell, p 356: "Faraday's Law of Induction."</ref> Together, these laws are enough to define the behavior of the electric field. However, since the magnetic field is described as a function of electric field, the equations of both fields are coupled and together form Maxwell's equations that describe both fields as a function of charges and currents.

Electrostatics

In the special case of a steady state (stationary charges and currents), the Maxwell-Faraday inductive effect disappears. The resulting two equations (Gauss's law <math>\nabla \cdot \mathbf{E} = \frac{\rho}{\varepsilon_0}</math> and Faraday's law with no induction term <math>\nabla \times \mathbf{E} = 0</math>), taken together, are equivalent to Coulomb's law, which states that a particle with electric charge <math>q_1</math> at position <math>\mathbf{x}_1</math> exerts a force on a particle with charge <math>q_0</math> at position <math>\mathbf{x}_0</math> of:<ref>Purcell, p7: "... the interaction between electric charges at rest is described by Coulomb's Law: two stationary electric charges repel or attract each other with a force proportional to the product of the magnitude of the charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.</ref> <math display="block">\mathbf{F}_{01} = \frac{q_1 q_0}{4\pi\varepsilon_0} \frac{\hat \mathbf{r}_{01}}{r_{01}^2} ,</math> where

- <math> \mathbf{F}_{01} </math> is the force on charged particle <math> q_0 </math> caused by charged particle <math> q_1 </math>.

- ε0 is the permittivity of free space.

- <math> \hat \mathbf{r}_{01} </math> is a unit vector directed from <math> \mathbf{x}_1 </math> to <math> \mathbf{x}_0 </math>.

- <math> r_{01} </math> is the distance from <math> \mathbf{x}_1 </math> to <math> \mathbf{x}_0 </math>.

Note that <math>\varepsilon_0</math> must be replaced with <math>\varepsilon</math>, permittivity, when charges are in non-empty media. When the charges <math>q_0</math> and <math>q_1</math> have the same sign this force is positive, directed away from the other charge, indicating the particles repel each other. When the charges have unlike signs the force is negative, indicating the particles attract. To make it easy to calculate the Coulomb force on any charge at position <math>\mathbf{x}_0</math> this expression can be divided by <math>q_0</math> leaving an expression that only depends on the other charge (the source charge)<ref name="Purcell">Purcell, Edward (2011). Electricity and Magnetism (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1139503556.</ref><ref name="Serway">Serway, Raymond A.; Vuille, Chris (2014). College Physics (10th ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 532–533. ISBN 978-1305142824.</ref> <math display="block">\mathbf{E}_{1} (\mathbf{x}_0) = \frac{ \mathbf{F}_{01} } {q_0} = \frac{q_1 }{4\pi\varepsilon_0} \frac{\hat \mathbf{r}_{01}}{r_{01}^2} ,</math> where

- <math>\mathbf{E}_{1} (\mathbf{x}_0) </math> is the component of the electric field at <math> q_0 </math> due to <math> q_1 </math>.

This is the electric field at point <math>\mathbf{x}_0</math> due to the point charge <math>q_1</math>; it is a vector-valued function equal to the Coulomb force per unit charge that a positive point charge would experience at the position <math>\mathbf{x}_0</math>. Since this formula gives the electric field magnitude and direction at any point <math>\mathbf{x}_0</math> in space (except at the location of the charge itself, <math>\mathbf{x}_1</math>, where it becomes infinite) it defines a vector field. From the above formula it can be seen that the electric field due to a point charge is everywhere directed away from the charge if it is positive, and toward the charge if it is negative, and its magnitude decreases with the inverse square of the distance from the charge.

The Coulomb force on a charge of magnitude <math>q</math> at any point in space is equal to the product of the charge and the electric field at that point <math display="block">\mathbf{F} = q\mathbf{E} .</math> The SI unit of the electric field is the newton per coulomb (N/C), or volt per meter (V/m); in terms of the SI base units it is kg⋅m⋅s−3⋅A−1.

Superposition principle

Due to the linearity of Maxwell's equations, electric fields satisfy the superposition principle, which states that the total electric field, at a point, due to a collection of charges is equal to the vector sum of the electric fields at that point due to the individual charges.<ref name="Serway" /> This principle is useful in calculating the field created by multiple point charges. If charges <math>q_1, q_2, \dots, q_n</math> are stationary in space at points <math>\mathbf{x}_1,\mathbf{x}_2,\dots,\mathbf{x}_n</math>, in the absence of currents, the superposition principle says that the resulting field is the sum of fields generated by each particle as described by Coulomb's law: <math display="block">\begin{align} \mathbf{E}(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{E}_1(\mathbf{x}) + \mathbf{E}_2(\mathbf{x}) + \mathbf{E}_3(\mathbf{x}) + \cdots = \frac 1 { 4\pi\varepsilon_0} \sum_{k=1}^N q_k \frac {\hat \mathbf{r}_k} {r_k^2} \end{align}</math> where

- <math>\mathbf{\hat r}_k</math> is the unit vector in the direction from point <math>\mathbf{x}_k</math> to point <math>\mathbf{x}</math>

- <math>r_k</math> is the distance from point <math>\mathbf{x}_k</math> to point <math>\mathbf{x}</math>.

Continuous charge distributions

The superposition principle allows for the calculation of the electric field due to a distribution of charge density <math>\rho(\mathbf{x})</math>. By considering the charge <math>\rho(\mathbf{x}')dv</math> in each small volume of space <math>dv</math> at point <math>\mathbf{x}'</math> as a point charge, the resulting electric field, <math>d\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{x})</math>, at point <math>\mathbf{x}</math> can be calculated as <math display="block">d\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{\rho(\mathbf{x}')}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\frac{\hat \mathbf{r}'}{ {r'}^2} dv</math> where

- <math>\hat \mathbf{r}'</math> is the unit vector pointing from <math>\mathbf{x}'</math> to <math>\mathbf{x}</math>.

- <math>r'</math> is the distance from <math>\mathbf{x}'</math> to <math>\mathbf{x}</math>.

The total field is found by summing the contributions from all the increments of volume by integrating the charge density over the volume <math>V</math>: <math display="block">\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0} \iiint_V \, \rho(\mathbf{x}') {\hat \mathbf{r}' \over { {r'}^2} } dv</math>

Similar equations follow for a surface charge with surface charge density <math>\sigma(\mathbf{x'})</math> on surface <math> S </math> <math display="block">\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0} \iint_S \, \sigma(\mathbf{x}') {\hat \mathbf{r}' \over { {r'}^2} } da</math> and for line charges with linear charge density <math>\lambda(\mathbf{x'})</math> on line <math> L </math> <math display="block">\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0} \int_L \,\lambda(\mathbf{x}') {\hat \mathbf{r}' \over { {r'}^2} } d \ell</math>

Electric potential

If a system is static, such that magnetic fields are not time-varying, then by Faraday's law, the electric field is curl-free. In this case, one can define an electric potential, that is, a function <math>\Phi</math> such that {{{1}}}<ref>gwrowe (8 October 2011). "Curl & Potential in Electrostatics" (PDF). physicspages.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2020.</ref> This is analogous to the gravitational potential. The difference between the electric potential at two points in space is called the potential difference (or voltage) between the two points.

In general, however, the electric field cannot be described independently of the magnetic field. Given the magnetic vector potential, A, defined so that <math>\mathbf{B} = \nabla \times \mathbf{A}</math>, one can still define an electric potential <math> \Phi</math> such that: <math display="block"> \mathbf{E} = - \nabla \Phi - \frac { \partial \mathbf{A} } { \partial t } ,</math> where <math>\nabla \Phi</math> is the gradient of the electric potential and <math>\frac { \partial \mathbf{A} } { \partial t }</math> is the partial derivative of A with respect to time.

Faraday's law of induction can be recovered by taking the curl of that equation <ref>Huray, Paul G. (2009). Maxwell's Equations. Wiley-IEEE. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-470-54276-7.[permanent dead link]</ref> <math display="block">\nabla \times \mathbf{E} = -\frac{\partial (\nabla \times \mathbf{A})} {\partial t} = -\frac{\partial \mathbf{B}} {\partial t} ,</math> which justifies, a posteriori, the previous form for E.

Continuous vs. discrete charge representation

The equations of electromagnetism are best described in a continuous description. However, charges are sometimes best described as discrete points; for example, some models may describe electrons as point sources where charge density is infinite on an infinitesimal section of space.

A charge <math>q</math> located at <math>\mathbf{r}_0</math> can be described mathematically as a charge density <math>\rho(\mathbf{r}) = q\delta(\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_0)</math>, where the Dirac delta function (in three dimensions) is used. Conversely, a charge distribution can be approximated by many small point charges.

Electrostatic fields

Electrostatic fields are electric fields that do not change with time. Such fields are present when systems of charged matter are stationary, or when electric currents are unchanging. In that case, Coulomb's law fully describes the field.<ref>Purcell, pp. 5–7.</ref>

Parallels between electrostatic and gravitational fields

Coulomb's law, which describes the interaction of electric charges: <math display="block">\mathbf{F} = q \left(\frac{Q}{4\pi\varepsilon_0} \frac{\mathbf{\hat{r}}}{|\mathbf{r}|^2}\right) = q \mathbf{E}</math> is similar to Newton's law of universal gravitation: <math display="block">\mathbf{F} = m\left(-GM\frac{\mathbf{\hat{r}}}{|\mathbf{r}|^2}\right) = m\mathbf{g}</math> (where <math display="inline">\mathbf{\hat{r}} = \mathbf{\frac{r}{|r|}}</math>).

This suggests similarities between the electric field E and the gravitational field g, or their associated potentials. Mass is sometimes called "gravitational charge".<ref>Salam, Abdus (16 December 1976). "Quarks and leptons come out to play". New Scientist. 72: 652.</ref>

Electrostatic and gravitational forces both are central, conservative and obey an inverse-square law.

Uniform fields

A uniform field is one in which the electric field is constant at every point. It can be approximated by placing two conducting plates parallel to each other and maintaining a voltage (potential difference) between them; it is only an approximation because of boundary effects (near the edge of the planes, electric field is distorted because the plane does not continue). Assuming infinite planes, the magnitude of the electric field E is: <math display="block"> E = - \frac{\Delta V}{d} ,</math> where ΔV is the potential difference between the plates and d is the distance separating the plates. The negative sign arises as positive charges repel, so a positive charge will experience a force away from the positively charged plate, in the opposite direction to that in which the voltage increases. In micro- and nano-applications, for instance in relation to semiconductors, a typical magnitude of an electric field is in the order of 106 V⋅m−1, achieved by applying a voltage of the order of 1 volt between conductors spaced 1 µm apart.

Electromagnetic fields

Electromagnetic fields are electric and magnetic fields, which may change with time, for instance when charges are in motion. Moving charges produce a magnetic field in accordance with Ampère's circuital law (with Maxwell's addition), which, along with Maxwell's other equations, defines the magnetic field, <math>\mathbf{B}</math>, in terms of its curl: <math display="block">\nabla \times \mathbf{B} = \mu_0\left(\mathbf{J} + \varepsilon_0 \frac{\partial \mathbf{E}} {\partial t} \right) ,</math> where <math>\mathbf{J}</math> is the current density, <math>\mu_0</math> is the vacuum permeability, and <math>\varepsilon_0</math> is the vacuum permittivity.

That is, both electric currents (i.e. charges in uniform motion) and the (partial) time derivative of the electric field directly contributes to the magnetic field. In addition, the Maxwell–Faraday equation states <math display="block">\nabla \times \mathbf{E} = -\frac{\partial \mathbf{B}} {\partial t}.</math> These represent two of Maxwell's four equations and they intricately link the electric and magnetic fields together, resulting in the electromagnetic field. The equations represent a set of four coupled multi-dimensional partial differential equations which, when solved for a system, describe the combined behavior of the electromagnetic fields. In general, the force experienced by a test charge in an electromagnetic field is given by the Lorentz force law: <math display="block">\mathbf{F} = q\mathbf{E} + q\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{B} .</math>

Energy in the electric field

The total energy per unit volume stored by the electromagnetic field is<ref name="Griffiths">Griffiths, D.J. (2017). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 357, eq. 8.5. ISBN 9781108420419.</ref> <math display="block"> u_\text{EM} = \frac{\varepsilon}{2} |\mathbf{E}|^2 + \frac{1}{2\mu} |\mathbf{B}|^2 </math> where ε is the permittivity of the medium in which the field exists, <math>\mu</math> its magnetic permeability, and E and B are the electric and magnetic field vectors.

As E and B fields are coupled, it would be misleading to split this expression into "electric" and "magnetic" contributions. In particular, an electrostatic field in any given frame of reference in general transforms into a field with a magnetic component in a relatively moving frame. Accordingly, decomposing the electromagnetic field into an electric and magnetic component is frame-specific, and similarly for the associated energy.

The total energy UEM stored in the electromagnetic field in a given volume V is <math display="block">U_\text{EM} = \frac{1}{2} \int_{V} \left( \varepsilon |\mathbf{E}|^2 + \frac{1}{\mu} |\mathbf{B}|^2 \right) dV \, .</math>

Electric displacement field

Definitive equation of vector fields

In the presence of matter, it is helpful to extend the notion of the electric field into three vector fields:<ref name="auto">Grant, I.S.; Phillips, W.R. (2008). Electromagnetism (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9.</ref> <math display="block">\mathbf{D} = \varepsilon_0 \mathbf{E} + \mathbf{P}</math> where P is the electric polarization – the volume density of electric dipole moments, and D is the electric displacement field. Since E and P are defined separately, this equation can be used to define D. The physical interpretation of D is not as clear as E (effectively the field applied to the material) or P (induced field due to the dipoles in the material), but still serves as a convenient mathematical simplification, since Maxwell's equations can be simplified in terms of free charges and currents.

Constitutive relation

The E and D fields are related by the permittivity of the material, ε.<ref>Bennet, G.A.G.; Arnold, Edward (1974). Electricity and Modern Physics (2 ed.). ISBN 0-7131-2459-8.</ref><ref name="auto"/>

For linear, homogeneous, isotropic materials E and D are proportional and constant throughout the region, there is no position dependence: <math display="block">\mathbf{D}(\mathbf{r}) = \varepsilon\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{r}) .</math>

For inhomogeneous materials, there is a position dependence throughout the material:<ref>Landau, Lev Davidovich; Lifshitz, Evgeny M. (1963). "68 the propagation of waves in an inhomogeneous medium". Electrodynamics of Continuous Media. Course of Theoretical Physics. Vol. 8. Pergamon. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-7581-6499-5. In Maxwell's equations… ε is a function of the co-ordinates.

</ref>

<math display="block">\mathbf{D}(\mathbf{r}) = \varepsilon (\mathbf{r})\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{r})</math>

For anisotropic materials the E and D fields are not parallel, and so E and D are related by the permittivity tensor (a 2nd order tensor field), in component form: <math display="block">D_i = \varepsilon_{ij} E_j</math>

For non-linear media, E and D are not proportional. Materials can have varying extents of linearity, homogeneity and isotropy.

Relativistic effects on electric field

Point charge in uniform motion

The invariance of the form of Maxwell's equations under Lorentz transformation can be used to derive the electric field of a uniformly moving point charge. The charge of a particle is considered frame invariant, as supported by experimental evidence.<ref name=":0">Purcell, Edward M.; Morin, David J. (2013-01-21). Electricity and Magnetism. pp. 241–251. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139012973. ISBN 9781139012973. Retrieved 2022-07-04. {{cite book}}: |website= ignored (help)</ref> Alternatively the electric field of uniformly moving point charges can be derived from the Lorentz transformation of four-force experienced by test charges in the source's rest frame given by Coulomb's law and assigning electric field and magnetic field by their definition given by the form of Lorentz force.<ref>Rosser, W. G. V. (1968). Classical Electromagnetism via Relativity. pp. 29–42. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-6559-2. ISBN 978-1-4899-6258-4.</ref> However the following equation is only applicable when no acceleration is involved in the particle's history where Coulomb's law can be considered or symmetry arguments can be used for solving Maxwell's equations in a simple manner. The electric field of such a uniformly moving point charge is hence given by:<ref>Heaviside, Oliver. Electromagnetic waves, the propagation of potential, and the electromagnetic effects of a moving charge.</ref>

<math display="block">\mathbf{E} = \frac q {4 \pi \epsilon_0 r^3} \frac {1- \beta^2} {(1- \beta^2 \sin^2 \theta)^{3/2}} \mathbf{r} ,</math>

where <math>q</math> is the charge of the point source, <math>\mathbf{r}</math> is the position vector from the point source to the point in space, <math>\beta</math> is the ratio of observed speed of the charge particle to the speed of light and <math>\theta</math> is the angle between <math>\mathbf{r}</math> and the observed velocity of the charged particle.

The above equation reduces to that given by Coulomb's law for non-relativistic speeds of the point charge. Spherically symmetry is not satisfied due to breaking of symmetry in the problem by specification of direction of velocity for calculation of field. To illustrate this, field lines of moving charges are sometimes represented as unequally spaced radial lines which would appear equally spaced in a co-moving reference frame.<ref name=":0" />

Propagation of disturbances in electric fields

Special theory of relativity imposes the principle of locality, that requires cause and effect to be time-like separated events where the causal efficacy does not travel faster than the speed of light.<ref>Naber, Gregory L. (2012). The Geometry of Minkowski spacetime: an introduction to the mathematics of the special theory of relativity. Springer. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-4419-7837-0. OCLC 804823303.</ref> Maxwell's laws are found to confirm to this view since the general solutions of fields are given in terms of retarded time which indicate that electromagnetic disturbances travel at the speed of light. Advanced time, which also provides a solution for Maxwell's law are ignored as an unphysical solution.

For the motion of a charged particle, considering for example the case of a moving particle with the above described electric field coming to an abrupt stop, the electric fields at points far from it do not immediately revert to that classically given for a stationary charge. On stopping, the field around the stationary points begin to revert to the expected state and this effect propagates outwards at the speed of light while the electric field lines far away from this will continue to point radially towards an assumed moving charge. This virtual particle will never be outside the range of propagation of the disturbance in electromagnetic field, since charged particles are restricted to have speeds slower than that of light, which makes it impossible to construct a Gaussian surface in this region that violates Gauss' law. Another technical difficulty that supports this is that charged particles travelling faster than or equal to speed of light no longer have a unique retarded time. Since electric field lines are continuous, an electromagnetic pulse of radiation is generated that connects at the boundary of this disturbance travelling outwards at the speed of light.<ref>Purcell, Edward M.; David J. Morin (2013). Electricity and Magnetism (Third ed.). Cambridge. pp. 251–255. ISBN 978-1-139-01297-3. OCLC 1105718330.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)</ref> In general, any accelerating point charge radiates electromagnetic waves however, non-radiating acceleration is possible in a systems of charges.

Arbitrarily moving point charge

For arbitrarily moving point charges, propagation of potential fields such as Lorenz gauge fields at the speed of light needs to be accounted for by using Liénard–Wiechert potential.<ref>Griffiths, David J. (2017). Introduction to electrodynamics (4th ed.). United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 454. ISBN 978-1-108-42041-9. OCLC 1021068059.</ref> Since the potentials satisfy Maxwell's equations, the fields derived for point charge also satisfy Maxwell's equations. The electric field is expressed as:<ref name=":1">Jackson, John David (1999). Classical electrodynamics (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 664–665. ISBN 0-471-30932-X. OCLC 38073290.</ref> <math display="block">\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{t}) = \frac{1}{4 \pi \varepsilon_0} \left(\frac{q(\mathbf{n}_s - \boldsymbol{\beta}_s)}{\gamma^2 (1 - \mathbf{n}_s \cdot \boldsymbol{\beta}_s)^3 |\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_s|^2} + \frac{q \mathbf{n}_s \times \big((\mathbf{n}_s - \boldsymbol{\beta}_s) \times \dot{\boldsymbol{\beta}_s}\big)}{c(1 - \mathbf{n}_s \cdot \boldsymbol{\beta}_s)^3 |\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_s|} \right)_{t = t_r}</math> where <math>q</math> is the charge of the point source, <math display="inline">{t_r}</math> is retarded time or the time at which the source's contribution of the electric field originated, <math display="inline">{r}_s(t)</math> is the position vector of the particle, <math display="inline">{n}_s(\mathbf{r},t)</math> is a unit vector pointing from charged particle to the point in space, <math display="inline"> \boldsymbol{\beta}_s(t)</math> is the velocity of the particle divided by the speed of light, and <math display="inline">\gamma(t)</math> is the corresponding Lorentz factor. The retarded time is given as solution of: <math>t_r=\mathbf{t}-\frac{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_s(t_r)|}{c}</math>

The uniqueness of solution for <math display="inline">{t_r}</math> for given <math>\mathbf{t}</math>, <math>\mathbf{r}</math> and <math>r_s(t)</math> is valid for charged particles moving slower than speed of light. Electromagnetic radiation of accelerating charges is known to be caused by the acceleration dependent term in the electric field from which relativistic correction for Larmor formula is obtained.<ref name=":1" />

There exist yet another set of solutions for Maxwell's equation of the same form but for advanced time <math display="inline">{t_a}</math> instead of retarded time given as a solution of:

<math>t_a=\mathbf{t}+\frac{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_s(t_a)|}{c}</math>

Since the physical interpretation of this indicates that the electric field at a point is governed by the particle's state at a point of time in the future, it is considered as an unphysical solution and hence neglected. However, there have been theories exploring the advanced time solutions of Maxwell's equations, such as Feynman Wheeler absorber theory.

The above equation, although consistent with that of uniformly moving point charges as well as its non-relativistic limit, are not corrected for quantum-mechanical effects.

Some common electric field values

Electric field infinitely close to a conducting surface in electrostatic equilibrium having charge density <math>\sigma</math> at that point is <math display="inline">\frac{\sigma}{\epsilon_0} \hat{x}</math> since charges are only formed on the surface and the surface at the infinitesimal scale resembles an infinite 2D plane. In the absence of external fields, spherical conductors exhibit a uniform charge distribution on the surface and hence have the same electric field as that of uniform spherical surface distribution.

See also

- Classical electromagnetism

- Relativistic electromagnetism

- Electricity

- History of electromagnetic theory

- Electromagnetic field

- Magnetism

- Teltron tube

- Teledeltos, a conductive paper that may be used as a simple analog computer for modelling fields

References

- Purcell, Edward; Morin, David (2013). Electricity and Magnetism (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press, New York. ISBN 978-1-107-01402-2.

- Browne, Michael (2011). Physics for Engineering and Science (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill, Schaum, New York. ISBN 978-0-07-161399-6.

External links

- Electric field in "Electricity and Magnetism", R Nave – Hyperphysics, Georgia State University

- Frank Wolfs's lectures at University of Rochester, chapters 23 and 24

- Fields Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine – a chapter from an online textbook

Lua error in Module:Authority_control at line 181: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).