Resultant force

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

In physics and engineering, a resultant force is the single force and associated torque obtained by combining a system of forces and torques acting on a rigid body via vector addition. The defining feature of a resultant force, or resultant force-torque, is that it has the same effect on the rigid body as the original system of forces.<ref>H. Dadourian, Analytical Mechanics for Students of Physics and Engineering, Van Nostrand Co., Boston, MA 1913</ref> Calculating and visualizing the resultant force on a body is done through computational analysis, or (in the case of sufficiently simple systems) a free body diagram.

The point of application of the resultant force determines its associated torque. The term resultant force should be understood to refer to both the forces and torques acting on a rigid body, which is why some use the term resultant force–torque.

The force equal to the resultant force in magnitude, yet pointed in the opposite direction, is called an equilibrant force.<ref name="FOOTNOTEHardy190423">Hardy 1904, p. 23.</ref>

Illustration

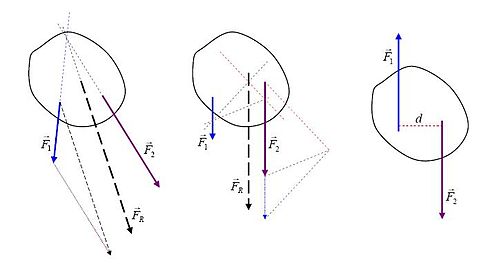

The diagram illustrates simple graphical methods for finding the line of application of the resultant force of simple planar systems.

- Lines of application of the actual forces <math> {\scriptstyle \vec{F}_{1}}</math> and <math>\scriptstyle \vec{F}_{2}</math> in the leftmost illustration intersect. After vector addition is performed "at the location of <math>\scriptstyle \vec{F}_{1}</math>", the net force obtained is translated so that its line of application passes through the common intersection point. With respect to that point all torques are zero, so the torque of the resultant force <math>\scriptstyle \vec{F}_{R}</math> is equal to the sum of the torques of the actual forces.

- Illustration in the middle of the diagram shows two parallel actual forces. After vector addition "at the location of <math>\scriptstyle\vec{F}_{2}</math>", the net force is translated to the appropriate line of application, whereof it becomes the resultant force <math>\scriptstyle \vec{F}_{R}</math>. The procedure is based on a decomposition of all forces into components for which the lines of application (pale dotted lines) intersect at one point (the so-called pole, arbitrarily set at the right side of the illustration). Then the arguments from the previous case are applied to the forces and their components to demonstrate the torque relationships.

- The rightmost illustration shows a couple, two equal but opposite forces for which the amount of the net force is zero, but they produce the net torque <math> \scriptstyle\tau = Fd </math> where <math>\scriptstyle d </math> is the distance between their lines of application. This is "pure" torque, since there is no resultant force.

Bound vector

A force applied to a body has a point of application. The effect of the force is different for different points of application. For this reason a force is called a bound vector, which means that it is bound to its point of application.

Forces applied at the same point can be added together to obtain the same effect on the body. However, forces with different points of application cannot be added together and maintain the same effect on the body.

It is a simple matter to change the point of application of a force by introducing equal and opposite forces at two different points of application that produce a pure torque on the body. In this way, all of the forces acting on a body can be moved to the same point of application with associated torques.

A system of forces on a rigid body is combined by moving the forces to the same point of application and computing the associated torques. The sum of these forces and torques yields the resultant force-torque.

Associated torque

If a point R is selected as the point of application of the resultant force F of a system of n forces Fi then the associated torque T is determined from the formulas

- <math> \mathbf{F} = \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{F}_i,</math>

and

- <math> \mathbf{T} = \sum_{i=1}^n (\mathbf{R}_i-\mathbf{R})\times \mathbf{F}_i. </math>

It is useful to note that the point of application R of the resultant force may be anywhere along the line of action of F without changing the value of the associated torque. To see this add the vector kF to the point of application R in the calculation of the associated torque,

- <math> \mathbf{T} = \sum_{i=1}^n (\mathbf{R}_i-(\mathbf{R}+k\mathbf{F}))\times \mathbf{F}_i. </math>

The right side of this equation can be separated into the original formula for T plus the additional term including kF,

- <math> \mathbf{T} = \sum_{i=1}^n (\mathbf{R}_i-\mathbf{R})\times \mathbf{F}_i - \sum_{i=1}^n k\mathbf{F}\times \mathbf{F}_i=\sum_{i=1}^n (\mathbf{R}_i-\mathbf{R})\times \mathbf{F}_i,</math>

because the second term is zero. To see this notice that F is the sum of the vectors Fi which yields

- <math>\sum_{i=1}^n k\mathbf{F}\times \mathbf{F}_i = k\mathbf{F}\times(\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{F}_i )=0,</math>

thus the value of the associated torque is unchanged.

Torque-free resultant

It is useful to consider whether there is a point of application R such that the associated torque is zero. This point is defined by the property

- <math> \mathbf{R} \times \mathbf{F} = \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{R}_i \times \mathbf{F}_i, </math>

where F is resultant force and Fi form the system of forces.

Notice that this equation for R has a solution only if the sum of the individual torques on the right side yield a vector that is perpendicular to F. Thus, the condition that a system of forces has a torque-free resultant can be written as

- <math>\mathbf{F}\cdot(\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{R}_i \times \mathbf{F}_i )=0.</math>

If this condition is satisfied then there is a point of application for the resultant which results in a pure force. If this condition is not satisfied, then the system of forces includes a pure torque for every point of application.

Wrench

The forces and torques acting on a rigid body can be assembled into the pair of vectors called a wrench.<ref>R. M. Murray, Z. Li, and S. Sastry, A Mathematical Introduction to Robotic Manipulation, CRC Press, 1994</ref> If a system of forces and torques has a net resultant force F and a net resultant torque T, then the entire system can be replaced by a force F and an arbitrarily located couple that yields a torque of T. In general, if F and T are orthogonal, it is possible to derive a radial vector R such that <math> \mathbf{R}\times\mathbf{F} = \mathbf{T} </math>, meaning that the single force F, acting at displacement R, can replace the system. If the system is zero-force (torque only), it is termed a screw and is mathematically formulated as screw theory.<ref>R. S. Ball, The Theory of Screws: A study in the dynamics of a rigid body, Hodges, Foster & Co., 1876</ref><ref>J. M. McCarthy and G. S. Soh, Geometric Design of Linkages. 2nd Edition, Springer 2010</ref>

The resultant force and torque on a rigid body obtained from a system of forces Fi i=1,...,n, is simply the sum of the individual wrenches Wi, that is

- <math> \mathsf{W} = \sum_{i=1}^n \mathsf{W}_i = \sum_{i=1}^n (\mathbf{F}_i, \mathbf{R}_i\times\mathbf{F}_i). </math>

Notice that the case of two equal but opposite forces F and -F acting at points A and B respectively, yields the resultant W=(F-F, A×F - B× F) = (0, (A-B)×F). This shows that wrenches of the form W=(0, T) can be interpreted as pure torques.

References

Lua error in mw.title.lua at line 318: bad argument #2 to 'title.new' (unrecognized namespace name 'Portal').

Sources

- Hardy, E. (1904). The Elementary Principles of Graphic Statics. B.T. Batsford. Retrieved 2024-02-02.